Representation in Tennessee Historical Markers

Candace Forbes Bright, PhD - RESET Research Fellow

Two years ago I relocated to Jonesborough, Tennessee—“Tennessee’s oldest town.” Jonesborough was founded in 1779, nearly two decades before Tennessee became a state and was the center of the abolitionist movement within the Confederate states. Jonesborough, now a heritage tourism site, focuses on historic preservation and the preservation of the Appalachian cultural tradition of storytelling. Located on West Main Street in historic downtown Jonesborough there is a historical marker for the site of Elihu Embree’s[1] printing of The Emancipator. This publication, also referred to as the abolition papers, was first printed in 1820 and is considered to be the first periodical solely dedicated to the abolition of slavery[2]. The Emancipator began with only six subscribers, but eventually accumulated over 2,000 once it gained out-of-state interest. The First Abolition Publications historical marker stands out among the many “he lived here” markers in the area. It reads:

First Abolition Publications Marker - sourced by hmdb.org

By Stanley and Terrie Howard, September 26, 2009

First Abolition Publications. On this site, in 1819-1820, were published The Manumission Intelligencer and The Emancipator. Edited and published by Elihu Embree and printed by Jacob Howard, these were the first periodicals in the United States devoted exclusively to abolition of human slavery.

Inspired by the research of colleagues on historical makers[3][4][5][6], I wanted to look deeper into the textual politics of historical markers in the region. Fortunately, in this process I found that (1) there is a complete database of historical markers available at The Historical Marker Database (www.hmdb.org) and (2) the last statewide study focused on Tennessee roadside historic markers was published in 1988. Jones’ (1988[7]) article, “An Analysis of National Register Listings and Roadside Historic Markers in Tennessee: A Study of Two Public History Programs,” analyzed 1,170 roadside markers across the state and found that markers devoted to black history or white women accounted for only 0.7% (n=8) and 0.8% (n=9), respectively, of all markers. Moreover, this meant that there were more markers devoted solely to David Crocket (0.9%) or to KKK founder Nathan Bedford Forrest (3%) than African Americans, women, or Native Americans. More recently, Abdallah’s (2015[8]) study, “More to the Story: Historical Narratives and the African American Past in Maury County, Tennessee” surveyed 27 historical markers in Maury County and found that 22 are dedicated to white residents and 5 mention African Americans. In other words, both studies find that these visual expressions of public history promote a white, protestant, male history of the state of Tennessee—African Americans and other minorities are largely omitted from commemorative sites.

Credit: Andrew Joyner

As historical roadside markers are meant to commemorate people, events, and places associated with the sites on which they are erected, they give communities a sense of identity—they deem what is important to remember. Public memory, however, is a social construct that is often dictated by the powerful. In this sense, markers are somewhat of a client/constituency history in which whites have control over memory and are able to sustain their power, often omitting the contributions of minorities and women. More importantly, exclusion in representation of the past limits present access to power.

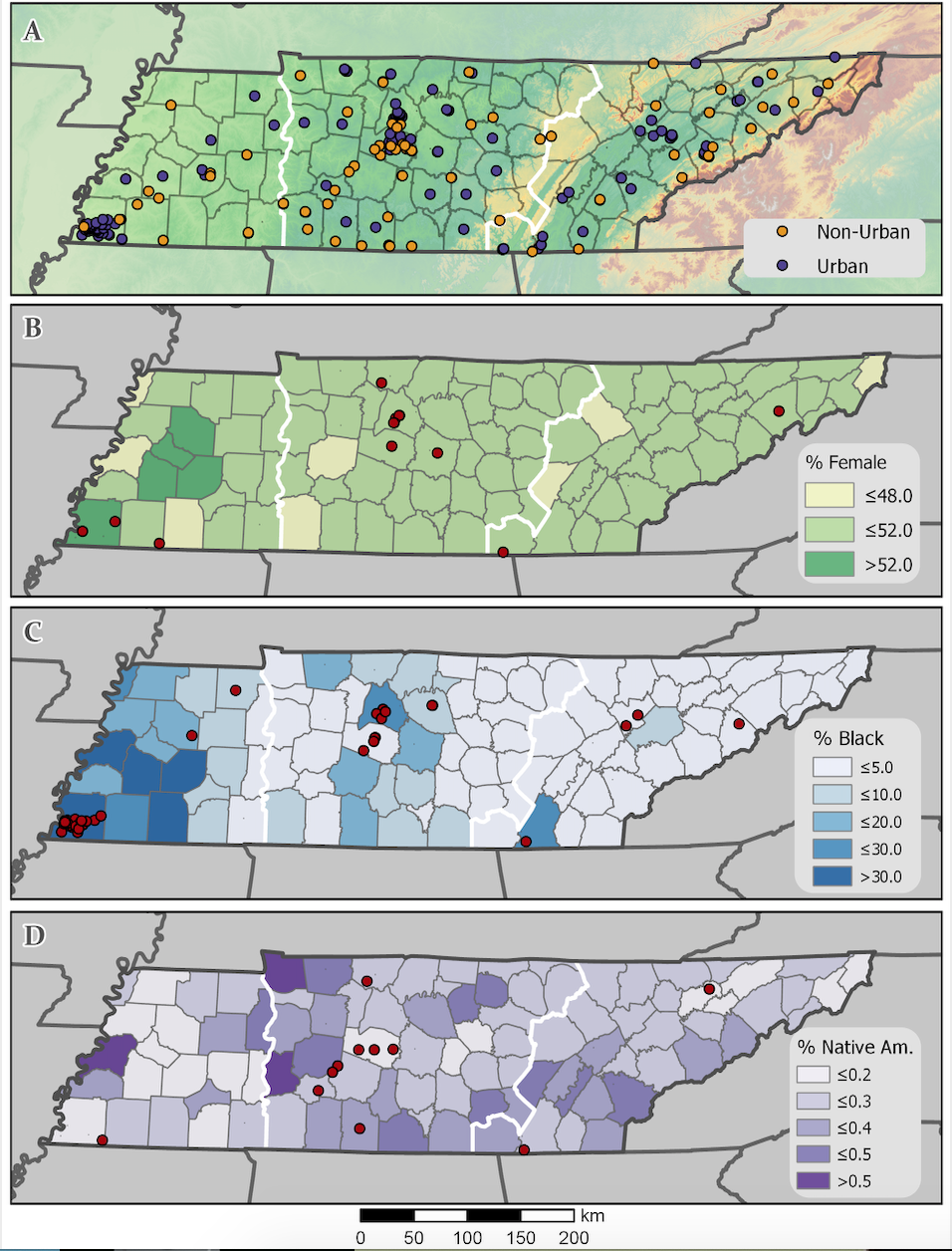

Jones cautiously stated, “Most recently, in 1987, as the result of newly conscious and organized constituency, Ida B. Wells, a late nineteenth-century civil rights activist and newspaper editor in Memphis, was memorialized with a marker. It is tempting to say that this represents the beginning of an increase in marker and listing behavior from the black or black-female constituency, but it is too early to tell.” This left the door open for the reproduction of Jones’ study and the assessment of his prediction. My colleagues (Dr. Kelly Foster, Associate Professor of Applied Sociology, ETSU; Dr. Andrew Joyner, Associate Professor of Geography, ETSU; and Oceane Tanney, Master’s Student of Applied Sociology, ETSU) and I then sought to update Jones’ study to see if just representation has improved in the three decades since Jones’ study. Focusing on the 313 historical roadside markers erected since 1988, we explored the frequencies by category presented in Jones’s article, the content of the signs and how they speak to societal values (and whose values are commemorated), and employ county-level demographics and funding source of these markers. We find that little progress has been made in promoting a more just representation in the past three decades. Like Jones and Abdallah before us, we find that we have failed as a state to promote the inclusion of a non-white history. Even in 2019, for instance, there are more historical markers focused solely on Nathan Bedford Forrest than all white women and Native Americans combined. Although we do see an increase in the share or signs devoted to Black History, the majority of those (not deemed to be ancillary to the purpose of the sign) are erected as part of one Memphis series marking school houses and are not distributed across the state.

Credit: Andrew Joyner

The first abolition publications marker, unfortunately, remains an outlier in Tennessee as the state’s historical roadside markers’ one-sided, value-biased representation of history largely omits entire ethnic and cultural groups, granting historical legitimacy to a view that neglects the true richness of the state’s history. This, of course, presents opportunities for Tennessee to challenge this dominant historical narrative and rectify this issue in the future. For instance, we mapped the historical markers across the state to demographic shares and we found that there are many counties across the state that have proportionally higher minority populations, but still few or no historical markers representing their history. In our research we specifically note opportunity around Shelby County, TN. Of the 69 historic markers in Shelby County, 26 represent Black History, two represent white female history, and one represents Native American history. However, if we look at the four counties surrounding Shelby County, all with black populations greater than 30% (Lauderdale, Haywood, Madison, and Hardeman), these counties have no markers representing any minority group or women. There are many such examples abound. In response, it is imperative that scholars and communities themselves, consciously advocate for a socially just representation of history and challenge the current commemoration. This is not unique to Tennessee, nor to the South, but draws light to social issues in our state.

[1] Embree, the publisher of The Emancipator, was a slaveholder and continued to own slaves until he died, despite publishing diametrically opposed viewpoints. He even notes in his publications that he struggled with opposing ideologies. He freed his slaves in his will.

[2] https://www.loc.gov/item/05033719/

[3] Alderman, D. H. (2012). “History by the spoonful” in North Carolina: the textual politics of state highway historical markers. southeastern geographer, 52(4), 355-373.

[4] Cook, M. (2014). The Textual Politics of Alabama's Historical Markers: Slavery and Emancipation on the Plantation. In Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers

[5] Hanna, S. P., & Hodder, E. F. (2015). Reading the signs: using a qualitative Geographic Information System to examine the commemoration of slavery and emancipation on historical markers in Fredericksburg, Virginia. cultural geographies, 22(3), 509-529.

[6] Cook, M. R. (2018). Textual Politics of Alabama’s Historical Markers: Slavery, Emancipation, and Civil Rights. Handbook of the Changing World Language Map, 1-31.

[7] Jones, J. B. (1988). An analysis of national register listings and roadside historic markers in Tennessee: A study of two public history programs. The Public Historian, 10(3), 19-30.

[8] Abdallah, J. E. (2015). More to the story: Historical narratives and the African American past in Maury County, Tennessee (Doctoral dissertation, Middle Tennessee State University).